No products in the cart.

At exactly 12:00 a.m. on Saturday, October 1, 1960, the Union Jack was lowered in Lagos, and a new flag of green, white, and green rose into the sky. It was Independence Day, and Nigeria was finally free from the British overlords.

However, independence did not come overnight. It was the result of resistance to the British invasion, decades of colonial rule, and years of struggle by courageous leaders and ordinary people alike.

This is the complete history of how Nigeria walked the long, difficult road to independence.

Contents

Nigeria Before the British

Long before Nigeria became a single country, it was home to diverse societies, each with its own way of life. In the north, the Hausa-Fulani had built thriving city-states such as Kano, Katsina, and Zaria. In the 19th century, these cities became part of the Sokoto Caliphate, an Islamic empire that stretched across the region. The caliphate had a sophisticated system of governance, with emirs ruling under the authority of the Sultan of Sokoto. It was also a centre of Islamic scholarship, with schools, mosques, and a vibrant culture.

In the West, the Yoruba people lived in powerful states such as Oyo, Ife, and Ijebu. The Oyo Empire, in particular, had a strong political structure with the Alaafin (king) at the centre, supported by a council of chiefs, known as Oyo Mesi.

Further south, the Benin Kingdom flourished, famous for its bronze artworks and highly organised government. The Oba of Benin ruled with absolute authority, supported by chiefs who oversaw trade, the military, and religious life.

In the east, the Igbo people had no kings but lived in self-governing communities. Decisions were made collectively, with elders, age grades, and councils playing important roles. This decentralised system gave the Igbo a strong sense of community participation. Along the coast, towns such as Lagos, Bonny, and Calabar engaged in trade with Europeans, first in slaves and later in palm oil and other goods.

These societies were not isolated. They traded with one another and with people as far away as North Africa and Europe. They produced art, developed systems of justice, and created enduring cultures. But their independence would not last forever.

The Coming of the British

European contact with Nigeria dates back to the 15th century, when Portuguese traders arrived on the coast. For centuries, the region was deeply involved in the transatlantic slave trade, with millions of men and women taken across the ocean. However, in 1807, Britain abolished the slave trade and shifted its interest to “legitimate commerce.” Palm oil, vital for the growing industries in Europe, became the new “gold.”

In 1851, the British bombarded Lagos, and 10 years later, in 1861, they annexed it, claiming it was to stop the slave trade but also to control commerce. Lagos grew into a bustling port city under colonial rule. From there, British influence spread inland.

The Royal Niger Company, led by George Taubman Goldie, signed treaties with local chiefs, giving it control over trade along the Niger River. By 1900, in a reaction to the atrocities of the Royal Niger Company in the country, the British Crown took direct control, creating the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria and the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria, alongside the Colony of Lagos.

In 1914, Lord Frederick Lugard, the Governor-General, merged these territories into one entity called “Nigeria.” The name itself was coined earlier in 1897 by journalist Flora Shaw, who would later marry Lugard. The amalgamation was done for the convenience of the colonial rulers, not for the benefit of the people.

Lugard introduced indirect rule, where traditional leaders were used to enforce British policies. While this system worked relatively well in the north, where emirs had authority, it caused tensions in the south, where communities like the Igbo did not traditionally have central rulers.

Seeds of Resistance

Colonial rule brought new opportunities but also many injustices. The British built roads, railways, and schools, but these were designed to serve their economic interests. Nigerians had little say in how they were governed. Taxes were imposed without representation, land was taken for foreign companies, and traditional rulers who resisted were removed.

Yet, the same colonial system that oppressed Nigerians also planted the seeds of resistance. Missionary schools introduced Western education, creating a new class of educated Nigerians. Many studied abroad, in Britain and the United States of America, where they were exposed to ideas of freedom, democracy, and self-determination. On their return, they began to question why Nigerians should remain subjects of a foreign power.

The press became a powerful weapon. Newspapers like the West African Pilot, founded by Nnamdi Azikiwe in November 1937, stirred nationalist feelings, criticised colonial policies, and spread the message of freedom. Writers and journalists used their pens to awaken the people.

Workers, too, played their part. The 1945 General Strike, led by Michael Imoudu, paralysed the economy and showed the strength of Nigerian labour. The Enugu Massacre of 1949, when colonial police killed striking coal miners, shocked the nation and deepened anger against the government. Ordinary Nigerians were no longer willing to accept injustice silently.

Constitutional Reforms

As pressure grew, the British introduced reforms, though always cautiously.

The 1922 Clifford Constitution introduced the elective principle, allowing Nigerians to elect four representatives—three in Lagos and one in Calabar. Though limited, it marked the first time Nigerians had a political voice.

The 1946 Richards Constitution aimed to unite the country by creating regional councils, but it gave little real power to Nigerians.

Then, the 1951 Macpherson Constitution allowed for regional assemblies and brought more Nigerians into government. It was more inclusive, but tensions between regions soon became clear, which would lead to the 1954 Lyttleton Constitution that created a true federal system, granting greater autonomy to the regions.

This marked an important step towards self-government.

These constitutions reflected Britain’s gradual approach. Independence would not be given suddenly, but Nigerians were determined to push for full self-rule.

The Nationalist Leaders

The independence struggle was driven by remarkable leaders who emerged in different regions.

Nnamdi Azikiwe, a fiery journalist, orator, and politician of the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC), inspired millions through his speeches and writings. He became a symbol of hope for many Nigerians. Also, Obafemi Awolowo, the Leader of the Action Group (AG) Party, championed education, social welfare, and development in the West. Awolowo introduced free primary education in the Western Region on January 7, 1955, a landmark achievement.

Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto and the Leader of the Northern People’s Congress (NPC), was cautious but influential. He prioritised the interests of the north while negotiating Nigeria’s independence.

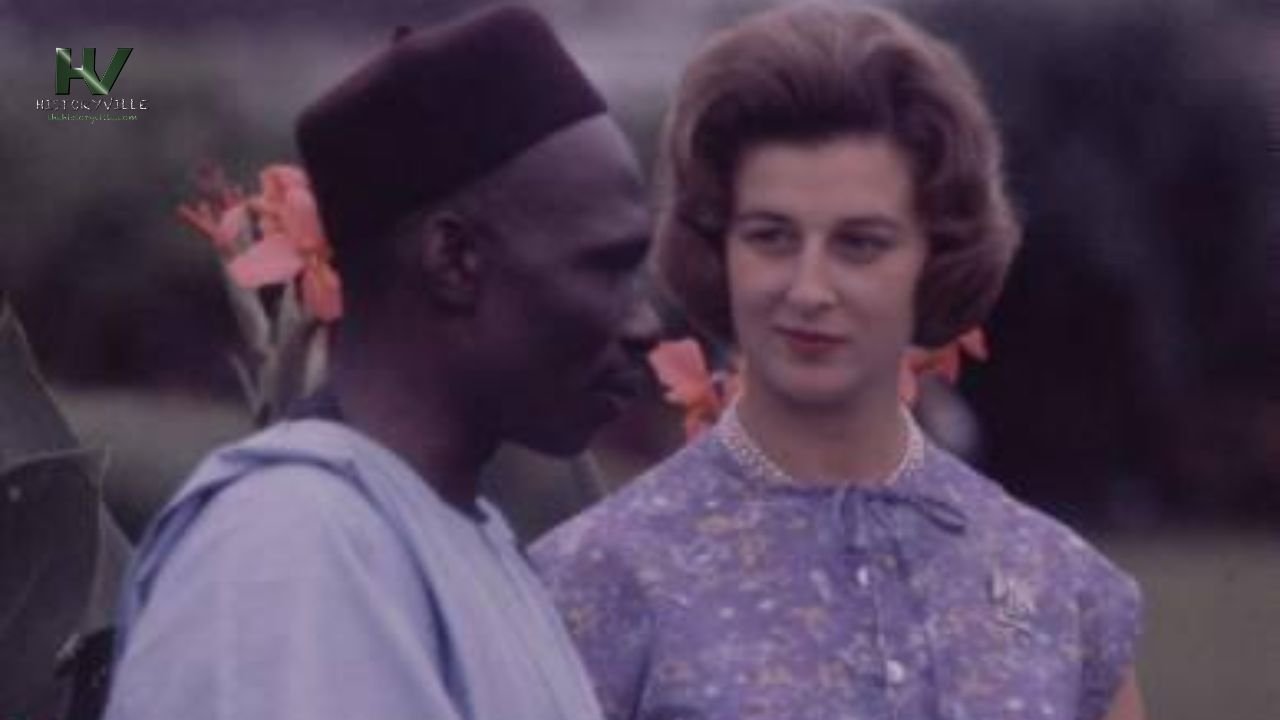

As was his deputy, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, a teacher-turned-politician, who was known for his diplomacy and calmness. He became Nigeria’s first Prime Minister on August 30, 1957.

Though these leaders often disagreed—sometimes bitterly—they shared the common goal of ending British colonial rule in Nigeria.

The Road to 1960

By the mid-1950s, the momentum was unstoppable. In 1957, the Eastern and Western Regions gained self-government. In 1959, the Northern Region followed. That same year, Nigeria held federal elections to prepare for independence. No single party won outright, so a coalition government was formed, with Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa as Prime Minister.

Finally, on October 1, 1960, Nigeria became independent.

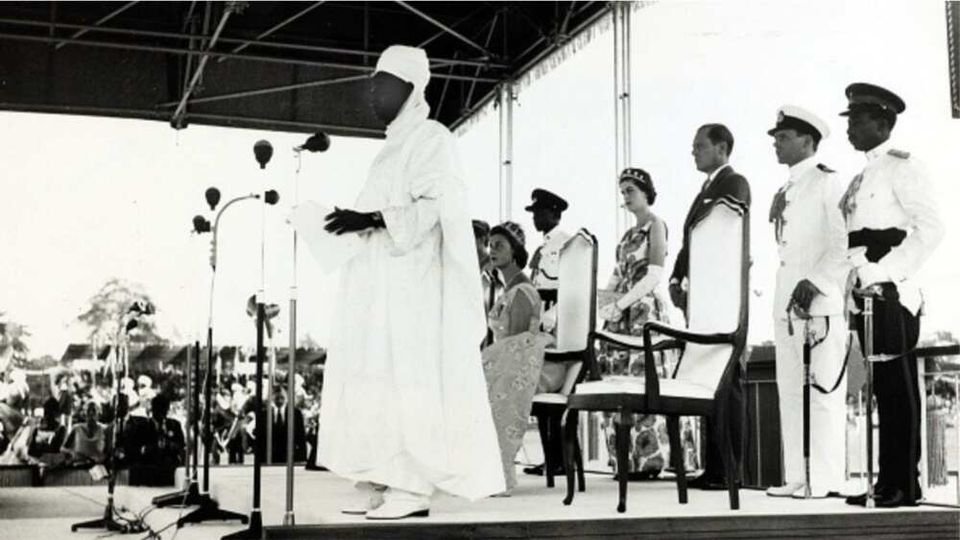

Across the country, celebrations erupted. The Union Jack was lowered, and the green-white-green flag was raised. In Lagos, Prime Minister Balewa declared:

“Today is Independence Day. The First of October 1960 is a date to which, for two years, Nigeria has been eagerly looking forward. At last, our great day has arrived, and Nigeria is now indeed an independent sovereign nation.

“We are grateful to the British officers whom we have known, first as masters, and then as leaders, and finally as partners; but always as friends.

“And so, with the words ‘God Save Our Queen’, I open a new chapter in the history of Nigeria and of the Commonwealth, and indeed, of the world.”

Nnamdi Azikiwe became Governor-General, and later Nigeria’s first President when the country became a republic on October 1, 1963.

Independence and Beyond

Independence was a moment of pride, but it also came with challenges. Nigeria was a vast country with more than 250 ethnic groups. Political parties were often tied to regional or ethnic interests: the NPC dominated the north, the NCNC in the east, and the AG in the west. This regionalism weakened national unity.

Economic disparities also created tensions. The north was less developed in education and infrastructure compared to the south. The colonial legacy of “divide and rule” made cooperation difficult.

now Tafawa-Balewa Square, Lagos, on the morning of Nigeria’s Independence Day, Saturday, October 1, 1960.

Within a few years, political instability grew. By 1966, Nigeria faced its first and second military coups, and soon after, the devastating 30-month civil war (1967–1970). Yet, despite these difficulties, the independence of 1960 remained a turning point—a testament to the determination of Nigerians to stay united and govern themselves.

Nigeria at 65: Reflections, the Way Forward

The road to Nigeria’s independence was long and difficult. It was marked by resistance, sacrifice, and determination. It saw the rise of visionary leaders, the struggle of workers, the boldness of journalists, and the courage of ordinary Nigerians who refused to remain subjects of colonial rule.

On October 1, 1960, a new nation was born. The dream of freedom had been realised. But the journey of building a united, just, and prosperous Nigeria was only beginning.

Yet, one cannot help but wonder: did independence truly heal the divisions of the colonial era, or did it merely pass them into Nigerian hands? Have the promises of freedom been fully realised, or are they still waiting to be achieved?

And most importantly, as we look back at the sacrifices of those who fought for freedom, what lessons should we carry forward to shape the Nigeria of tomorrow?

Your support can make a world of difference in helping us continue to bring Nigeria’s rich history to life! By donating to HistoryVille, you’re directly contributing to the research, production, and storytelling that uncover the incredible stories of our past. Every donation fuels our mission to educate, inspire, and preserve our heritage for generations to come.

Please stay connected with us through our social media handles and make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel. Together, let’s keep the stories of Nigeria’s past alive.

Leave a Reply

View Comments