No products in the cart.

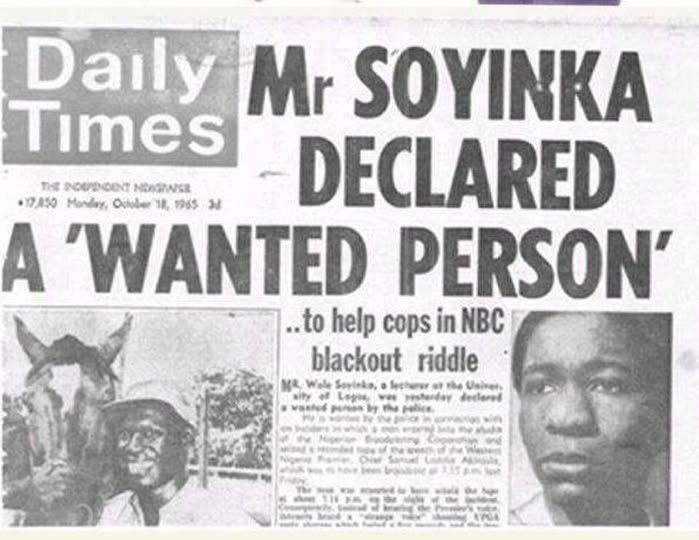

On the night of October 15, 1965, something extraordinary happened. An unknown gunman broke into the Western Nigerian Broadcasting Service in Ibadan. At gunpoint, he ordered the officer on duty to play a tape he had brought with him—a bold message demanding that the Premier, Chief Samuel Ladoke Akintola, resign immediately and leave office.

The region erupted. Akintola’s supporters were furious, the police launched a manhunt, and the mysterious gunman vanished. For days, no one knew who he was or where he had gone.

However, Wole Soyinka, a young playwright, poet, and activist, was arrested 12 days later by the Police and brought before Justice Kayode Eso.

But what later happened?

Well, 60 years later, we revisit the story in this article.

Contents

The Wild West

To grasp the gravity of what happened that night, one must understand the Western Region of Nigeria in 1965. The region was once the envy of the federation, led in its golden years by Chief Obafemi Awolowo, who introduced free education and welfare programmes. However, by the early 1960s, things had begun to fall apart. The alliance between Awolowo and his deputy, Akintola, had crumbled into enmity. Akintola broke away to form his own party, the Nigerian National Democratic Party, while Awolowo’s loyalists remained with the Action Group.

Elections became warfare. Thugs roamed the streets. Ballot boxes were stuffed or burnt. The region earned the nickname “The Wild Wild West.” Violence flared in towns like Ogbomosho, Ibadan, and Oyo. People died for daring to vote. Amid this chaos, Premier Akintola clung to power, insisting that order would soon return. His government prepared a radio broadcast to declare victory and call for peace.

But peace was far away.

Many Nigerians felt that democracy had been murdered. The Western Region had become a land of bitterness, its people disillusioned by leaders who spoke of progress but practised oppression. In such a climate, it was not hard to imagine a brave or desperate soul deciding to seize the microphone and give voice to the truth.

The Night of the Broadcast

It was on the night of October 15, 1965, at the Western Nigeria Broadcasting Service, WNBS, Ibadan. The officer on duty, Akinwande Oshin, was preparing to air Akintola’s recorded message at precisely 7 p.m. The tape had been checked and queued.

Then the studio door opened.

A man entered, revolver in hand. He was described later as unmasked and bearded. Calmly but firmly, he instructed Oshin to hand over the Premier’s tape. Instead, he handed over another reel and ordered that it be played immediately. Oshin obeyed. As the new tape rolled, a different voice filled the airwaves—angry, passionate, defiant.

“This is a voice,” it declared. “The true voice of the people of Western Nigeria and all the voices are saying very simply…“

“Akintola, get out; Akintola, get out and take with you your band of renegades who have lost with you any pretence, and have become nothing but murdering beasts.

“Take with you your goons, who would sooner kill and maim than acknowledge that you are all now outcasts to human society. The lawful government of Western Nigeria is the UPGA government, elected by the people of the West.

“Let every self-seeking impostor get out now before the people, losing patience, wash the streets in their polluted blood. Get out, and take with you your lepers, your things, your army, your police, in their kits and armoured cars, frightening old women in the markets, pumping bullets through the doors of female students and dragging their brave bodies down concrete steps because they dare protest.

“The children loathe you; mothers curse you; all men despise you, and the youths of this country long for the moment when your presence will no longer pollute their home for a decent future.

“In the name of Oduduwa and our generation, get out! Before the frustration of ten million people, their anger and their justice in an all-consuming fire come over your heads.

“And to you, the Police, who think you merely obey orders; to you, the Army, who commit those crimes in the name of obedience, and to you, our Obas, who have lost shame, honour and dignity; to you, the civil servants, radio, press, who think more of your bellies than the legacy you have bequeathed to our generation; to you, the intellectuals, who sit while acts of horror are committed before your eyes; to you, priests, bishops, imams, who do not use your pulpits for the benefit of our generation: we remind you that the floods that have waited many years to break loose will not have the leisure to choose between the hovels and the palaces….”[1]

In minutes, the act was done. The gunman picked up his revolver, ordered Oshin not to move, and slipped out. No gunshots were fired. No one was hurt. Yet the deed reverberated across the West like thunder.

By the next morning, the Unknown Gunman had become an instant legend.

But in a country as politicised as Nigeria, legends seldom last without suspects.

The Arrest of Wole Soyinka

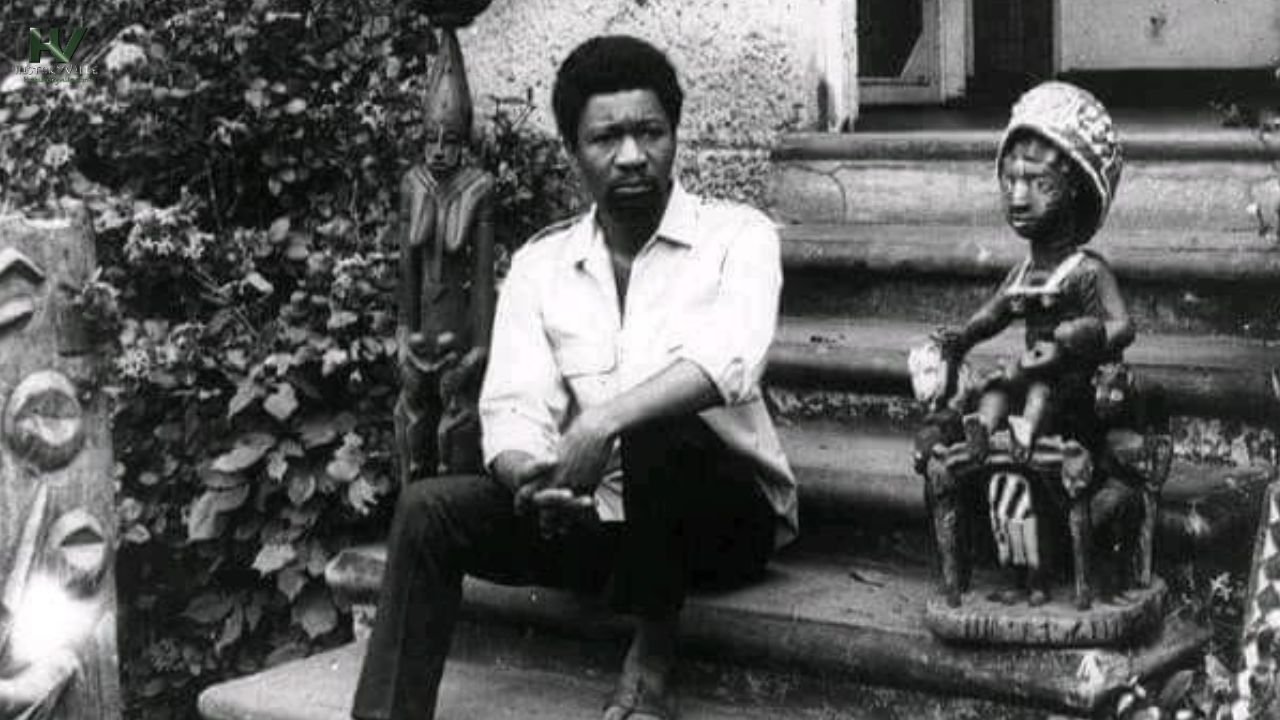

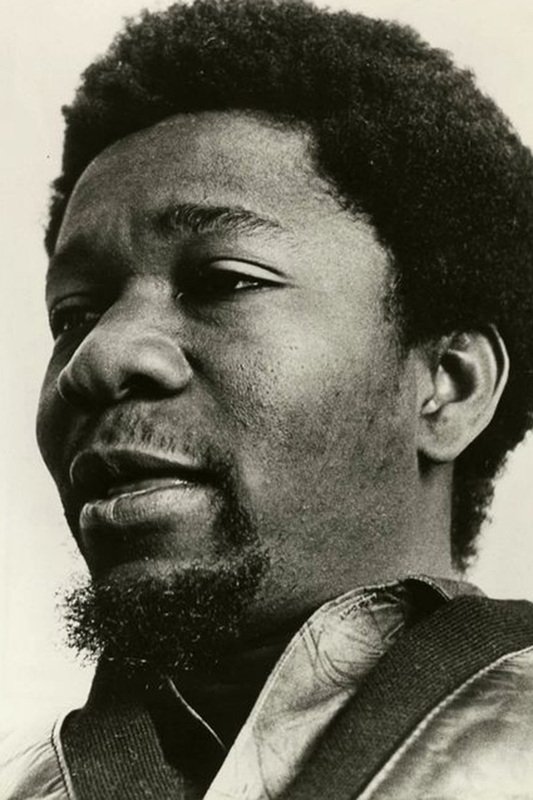

Among the shocked citizens was a 31-year-old lecturer and playwright at the University of Ibadan, Wole Soyinka. Already known for his biting plays and essays, Soyinka was an outspoken critic of corruption and tyranny. His works mocked political greed, and his stage had become a weapon of protest.

Within 12 days of the incident, the police arrested Soyinka. They accused him of being the Unknown Gunman. The evidence was circumstantial, but the accusation alone was sensational. It made perfect political sense to the authorities: who else but a fearless intellectual like Soyinka would dare to challenge power so publicly?

Wole Soyinka was taken into custody and charged with treason and the theft of government property, the Premier’s broadcast tape. He denied all charges, insisting he had nothing to do with the incident.

For many Nigerians, it seemed impossible that a scholar and playwright could also be a gun-wielding rebel. For others, it made perfect sense.

The Trial of Wole Soyinka

The trial began before Justice Kayode Eso, a 40-year-old brilliant jurist who would later become one of Nigeria’s most respected judges. From the start, the case attracted nationwide attention. Crowds gathered daily outside the courthouse in Ibadan, while journalists filled the gallery. Some came expecting to see a conviction; others hoped to witness justice triumph over politics.

The prosecution called witnesses from the radio station who testified that the intruder was unmasked, bearded, and carried a revolver. They claimed they could recognise Wole Soyinka as that man. The evidence seemed convincing until the defence called Professor Axworthy, the Head of Department at the University of Ibadan, who stated under oath that he had seen Soyinka earlier that same evening.

At around five o’clock, Axworthy said, they had attended a departmental meeting. Wole Soyinka, he recalled, was clean-shaven.

The courtroom fell silent. The prosecution’s entire case rested on the physical description of the intruder. How could a clean-shaven man at five p.m. become bearded by seven? Unless the witnesses were mistaken, or the bearded gunman was someone else entirely?

Justice Eso later wrote in his memoir The Mystery Gunman:

“While I can understand a bearded man at five o’clock in the evening becoming clean-shaven at 7 p.m., I cannot unravel the mystery of a clean-shaven man at 5 p.m. becoming bearded at 7 p.m. except he is somehow masked.”[2]

It was the turning point. The judge concluded that the prosecution had failed to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. Wole Soyinka was, accordingly, discharged and acquitted. The trial was over.

The Aftermath: The Making of a Myth

Though legally free, Wole Soyinka could not escape the shadow of the Unknown Gunman. The government’s embarrassment lingered, and his name became synonymous with the mysterious act. For years, people whispered about whether he had truly done it. The absence of proof only deepened the intrigue.

Wole Soyinka, for his part, refused to clarify. He neither confirmed nor denied the allegations. Instead, he let the myth breathe. In interviews, when journalists pressed him, he would smile and quip, “If I had done it, I’d probably have done it better.”

In his prison memoir The Man Died (1972), Wole Soyinka reflected on his ordeal and on Nigeria’s decay, but he avoided the details of the Ibadan incident. Later, in his autobiography You Must Set Forth at Dawn, he finally addressed the story obliquely:

“One day, some people claimed I had entered a radio station with a gun. It became a myth. The truth is always less dramatic than legend.”

By refusing to settle the question, he elevated it. The Unknown Gunman became part of the Wole Soyinka legend, a metaphor for intellectual courage, rebellion, and moral audacity. Whether he had held the gun or not no longer mattered; the idea that he could have been was enough.

The Symbolism of the Unknown Gunman

Over the decades, the story of Wole Soyinka and the Unknown Gunman has evolved into more than just history; it has become an allegory. It speaks to the eternal struggle between truth and power, between those who control the microphone and those who snatch it away to talk about truth to the people.

To some, the Unknown Gunman is a hero, a symbol of defiance against tyranny. To others, he is an outlaw, an emblem of the chaos that helped unravel Nigeria’s first attempt at democracy. Yet, for most, he remains a ghostly figure who straddles both worlds: the intellectual with a gun, the poet with a cause, the writer who refused to whisper.

It is fitting, perhaps, that Wole Soyinka became Nigeria’s first Nobel Laureate in Literature two decades later, in 1986. His works continued to interrogate power, corruption, and human conscience. From the stage to the page, he wielded his pen like a weapon, proof that words, too, can hijack the airwaves.

Sixty years later, the Ibadan radio incident still haunts the collective imagination. Historians and journalists continue to debate what truly happened that night. Did Wole Soyinka really enter the broadcasting house? Was he framed by political enemies seeking to silence a radical voice? Or was the act a masterstroke of protest theatre, art meeting rebellion in one daring performance?

We may never know.

Was Wole Soyinka the Unknown Gunman?

So, who was the Unknown Gunman who stormed the Ibadan broadcasting house in 1965? Was it truly Wole Soyinka, the fiery lecturer who would one day become a Nobel Laureate? Or was it another man entirely, someone history forgot, whose boldness was wrongly attributed to the playwright?

And if it was Wole Soyinka, what does that say about the power of conscience? Can rebellion ever be justified when truth is under siege? When a government silences its people, is it wrong for a citizen to seize the microphone?

Or perhaps the greater question is this: does it even matter anymore who held the gun, when the real weapon was the message that rang out across the night, the message that power could be challenged, that truth could find a voice, that silence could be broken?

For Wole Soyinka, the legend of the Unknown Gunman became inseparable from his life story. He went on to win the Nobel Prize, to write plays that shook dictatorships, and to survive imprisonment and exile. But somewhere in the folds of Nigeria’s history, that night in Ibadan still lingers like an unresolved question, half history, half myth.

The Western Region crisis deepened after the broadcast incident involving the unknown gunman. Violence exploded in towns and villages as rival political thugs fought openly in the streets. Houses were burnt; opponents were hunted down, and the entire region seemed to collapse into anarchy.

The conflict became known as Operation Wetie.

Your support can make a world of difference in helping us continue to bring Nigeria’s rich history to life! By donating to HistoryVille, you’re directly contributing to the research, production, and storytelling that uncover the incredible stories of our past. Every donation fuels our mission to educate, inspire, and preserve our heritage for future generations.

Please stay connected with us through our social media handles and make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel. Together, let’s keep the stories of Nigeria’s past alive.

Leave a Reply

View Comments