No products in the cart.

On the morning of January 15, 1966, Nigeria woke to a sudden end to its short experiment with civilian rule. Barely six years after independence, a group of young military officers struck at the heart of the state, killing senior political leaders and top army officers. To many Nigerians at the time, the coup came as a shock; to others, it felt like an eruption long foretold. Sixty years on, the first military coup remains a defining moment in Nigeria’s history, setting the country on a path it has struggled to escape.

The men who struck claimed they were driven by anger at corruption, regional rivalry, and the breakdown of law and order. Nigeria’s First Republic was deeply divided, poisoned by disputed elections, political violence, and mutual suspicion among its leaders. The coup plotters saw themselves as patriots stepping in to save the nation from collapse. Yet their actions, and the pattern of killings that morning, raised troubling questions about motive, bias, and the true meaning of their intervention.

The events of January 15, 1966, reshaped power, hardened ethnic fears, and opened the door to countercoups, civil war, and decades of instability.

Contents

A Background on Nigeria’s First Military Coup

January 15, 1966, was the violent climax of a First Republic already in visible decay. Nigeria’s independence on October 1, 1960, had carried immense hope, but the promise of self-rule soon gave way to intense regional rivalry, ethnic suspicion, and a political culture driven more by power than by principle. The federation was loosely held together by three dominant regions, North, West and East, each controlled by powerful political parties whose loyalty was first to the region, then to the nation.

By the mid-1960s, the political system had become dangerously unstable. Elections were openly manipulated, opposition voices were silenced, and state resources were treated as personal spoils. Nowhere was this collapse more evident than in the Western Region, where the 1965 election triggered widespread violence. Homes were burnt, opponents were hunted, and the phrase “Operation Wetie” became shorthand for lawlessness. For ordinary Nigerians, faith in civilian leadership steadily eroded.

The military, trained under British discipline and still enjoying public respect, watched this breakdown with growing frustration. Many officers believed the politicians had betrayed the ideals of independence. January 15, 1966, was, therefore, conceived by its planners not merely as a seizure of power, but as a corrective moment. An attempt, as they saw it, to halt Nigeria’s slide into chaos. However, the decision to intervene would unleash forces far more destructive than those they hoped to suppress.

The January Boys

The officers behind the January 15, 1966, military coup came to be known as the “January Boys.” A loose but committed group of mostly young, middle-ranking officers. They were products of a new Nigeria: educated, confident, and impatient with what they regarded as the moral bankruptcy of the political elite. Many had trained abroad, absorbed nationalist ideas, and returned home convinced that Nigeria deserved better leadership.

Among them were Majors Emmanuel Ifeajuna, Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, Adewale Ademoyega, Chris Anuforo, Donatus Okafor, Humphrey Chukwuka and Captain Ben Gbulie. Though they differed in temperament and background, they shared a core belief: that Nigeria was being destroyed by corruption, nepotism, tribalism, and political greed, and that the military had a duty to intervene.

Ideologically, the January Boys did not form a coherent political movement in the modern sense. There was no detailed manifesto for governance beyond vague promises of discipline, unity and national rebirth. Their thinking was shaped by a moral absolutism common among young revolutionaries: a belief that removing “bad leaders” would automatically cleanse the system. They underestimated the complexity of Nigeria’s divisions and overestimated their own ability to control the consequences of violence.

Crucially, the plotters believed they were acting above ethnic interest. But the pattern of killings on January 15, 1966, would later undermine this claim and fuel enduring controversy. Whether intended or not, the coup came to be interpreted through ethnic lenses, with devastating consequences for national unity.

How the January Coup Happened

In the early hours of January 15, 1966, Nigeria was struck by a coordinated military uprising. The plotters moved simultaneously in key centres of power – Lagos, Ibadan, Kaduna and other strategic locations. Their objective was simple but brutal: neutralise political leaders and senior military officers seen as symbols of corruption and obstruction.

In Lagos, Prime Minister Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was abducted and later killed. Finance Minister Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh was also murdered. Senior army officers, including Brigadiers Samuel Ademulegun and Zakariya Maimalari, Colonel Kur Mohammed, and Lieutenant-Colonels Abogo Lagerma, James Yakubu Pam, and Arthur Chinyelu Unegbe, were cut down in their prime. Similar operations unfolded elsewhere, though not all went according to plan.

The coup, however, suffered from fatal weaknesses. Communication between units was poor, coordination was uneven, and several key officers either resisted or escaped. In some areas, soldiers refused to obey orders they did not fully understand. By the end of January 15, 1966, the coup had shaken the country but failed to establish a clear new authority.

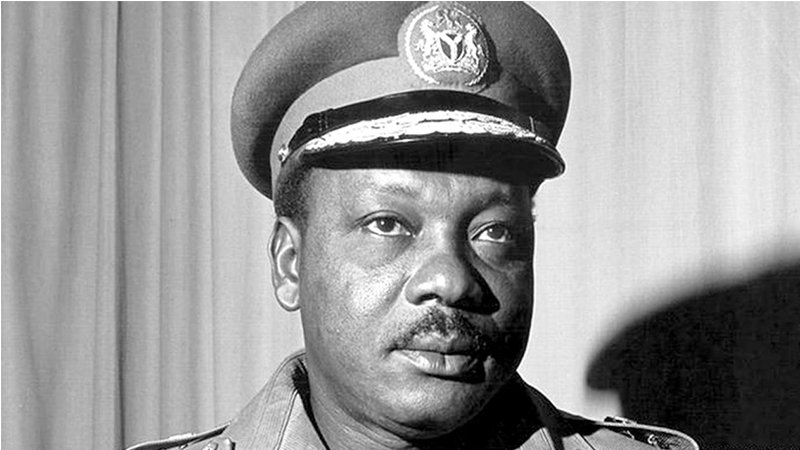

This failure proved decisive. What was meant to be a swift, cleansing intervention became an incomplete revolution; violent enough to destroy civilian rule, but too disorganised to establish a new political order. However, the most senior officer in the Army High Command, Major-General Johnson Thomas Aguiyi-Ironsi, exploited this vacuum and took power as Nigeria’s first military head of state on January 16, 1966.

Who Led Nigeria’s First Military Coup?

The question of leadership in the January 15, 1966, coup remains contested. Public memory often places Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu at the centre, largely because of his prominent role in Kaduna and his later speeches. However, historical evidence shows that leadership was collective rather than singular.

Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna played a crucial role in planning and execution, particularly in Lagos, where political power was concentrated. Adewale Ademoyega and other officers were deeply involved in shaping the strategy. Decisions and responsibilities were shared, and authority devolved across locations.

Nzeogwu emerged as the most visible figure because his operations were decisive and successful. Also, because he gave a speech to justify their insurrection. However, to reduce the coup to a single leader oversimplifies a complex conspiracy involving multiple actors, each operating with partial autonomy.

This lack of unified command partly explains why the coup collapsed into confusion. Leadership ambiguity on January 15, 1966, would prove as damaging as the violence itself.

The Aftermath of January 15, 1966

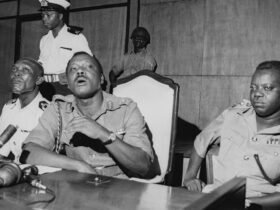

The immediate aftermath of January 15, 1966, was marked by fear, uncertainty and deepening suspicion. Although civilian leaders were dead, the coup plotters failed to consolidate power. Senior officers who survived moved quickly to restore order, and within days, Major-General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi emerged as Head of the Army and de facto ruler of Nigeria.

Nigeria’s First Military Head-of-State (January 16, 1966 – July 29, 1966).

Aguiyi-Ironsi’s decision to suspend the constitution and assume control marked the formal end of the First Republic. While he presented his rule as temporary, his policies, particularly the unification decree of May 24, 1966, intensified regional resentment, especially in the North. Many northerners viewed January 15 as an ethnically selective coup and Aguiyi-Ironsi’s government as its continuation.

These tensions exploded in July 1966 with a bloody countercoup that claimed the general’s life and plunged Nigeria deeper into crisis. What began on January 15, 1966, as an attempt to save the nation ultimately paved the road to civil war.

January 15, 1966: 60 Years On

It has been 60 years since January 15, 1966, yet modern Nigeria has never fully recovered. What began as an intervention by idealistic young officers ended Nigeria’s First Republic, shattered trust among its citizens, and permanently altered the relationship between the military and politics.

The coup destroyed civilian supremacy at a stroke and introduced a dangerous idea into the national psyche: that the gun, not the ballot, could be a legitimate tool for political correction. Once that door was opened, it could not easily be shut.

The tragedy of January 15, 1966, deepened ethnic suspicions, especially as its killings appeared uneven and its aftermath failed to reassure a frightened nation. The July countercoup, the pogroms, and ultimately, the civil war, all flowed from the unresolved questions of that unprecedented military rebellion.

Each military regime that followed, whether well-intentioned or ruthless, carried the imprint of that first intervention. Even Nigeria’s return to civilian rule decades later has remained haunted by the habits, structures, and mistrust born on that morning.

Sixty years on, remembering January 15, 1966, is how unresolved political failure invites violent solutions. As a result, Nigeria’s present struggles with governance, legitimacy, and national cohesion cannot be fully understood without confronting the events of that day honestly and without sentiment.

If you want to go beyond headlines and how the coup unfolded hour by hour, then you can get the book, A Carnage Before Dawn. It offers a carefully researched, vividly told account of January 15, 1966, through a storytelling style that will keep you glued to the book’s pages.

You can get the e-book here and the paperback here.

Leave a Reply

View Comments