No products in the cart.

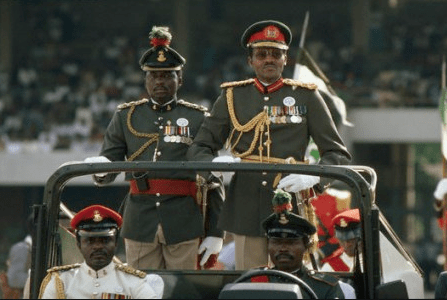

It has been 40 years since Nigeria’s fifth military head of state, Major-General Muhammadu Buhari, was overthrown in a palace coup on August 27, 1985. Buhari, the stern-faced soldier who had seized power barely 20 months earlier, found his rule abruptly cut short within the very walls of Dodan Barracks. The takeover, led by his own Chief of Army Staff, Major-General Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida, was swift, silent, and precise. There were no gun battles in the streets, yet the shock resounded across the nation.

For many Nigerians, the moment was as mystifying as it was sudden. Buhari had risen on the promise of discipline and reform, yet his reign was defined by strict decrees, economic hardship, and an iron-fisted War Against Indiscipline. Babangida, the man who once stood at his side, now stood in his place. Radio Nigeria became the nation’s only window into the unfolding drama as the former Chief of Army Staff addressed the country, justifying the coup as a necessary rescue mission for a struggling nation.

Forty years later, the events of that day still raise pressing questions. Was the coup truly a salvation, or simply another power shift within a turbulent era of military politics? How did trusted allies turn into political rivals overnight? And what can Nigeria’s present-day leaders learn from a decisive change that altered the country’s course?

Exactly 40 years on, we remember the palace coup against Muhammadu Buhari in this article.

Contents

How the Coup Was Planned Out

By the middle of 1985, Nigeria’s Supreme Military Council was no longer a united body. Major-General Muhammadu Buhari, who had seized power from President Shehu Shagari in December 1983, ruled with an iron fist and an austere economic programme. His administration had enforced strict import restrictions, closed the country’s borders to curb smuggling, and clamped down heavily on political dissent. While these measures won him the admiration of citizens who longed for discipline in public life, they also bred resentment among certain senior officers and sections of the political elite. The economy was strained, public morale was low, and the military’s inner circle was becoming increasingly uneasy with Buhari’s style of governance.

Major-General Ibrahim Babangida, then Chief of Army Staff, emerged as the focal point for discontent. Known for his charm, political skill, and extensive network within the armed forces, Babangida quietly began to assemble a coalition of dissatisfied officers. His plan was not to stage a noisy, violent overthrow but to execute a swift, clinical takeover at the very heart of power — a true palace coup. The groundwork involved careful intelligence gathering, discreet persuasion of key commanders, and securing the loyalty of units stationed in Lagos, particularly those responsible for protecting Dodan Barracks, the seat of government. Meetings were held behind closed doors in officers’ messes and private residences, always in small groups to avoid suspicion.

The coup was scheduled for the early hours of August 27, 1985, when the chances of resistance would be minimal. At dawn, a great while before morning, troops loyal to Babangida quietly took control of strategic positions in Lagos: Army Headquarters, communication centres, and access roads leading to Dodan Barracks. By dawn, the seat of government was completely encircled. Buhari was isolated and effectively cut off from the outside world. He was then placed under house arrest.

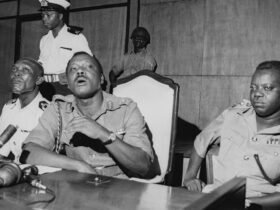

Soon after, Major-General Ibrahim Babangida landed in Lagos from Minna and appeared on national radio to inform the nation that the “rigid” policies of the former government were being replaced with a more “humane” and “dynamic” approach to governance. With those statements, the Babangida era began.

The Players of August – The Men Behind the 1985 Palace Coup

The August 1985 coup was not the work of a single mastermind but the result of a tightly knit network of officers bound by trust, ambition, and a shared belief that Buhari’s rule had become unsustainable. At the centre of this web was Major-General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, Nigeria’s Chief of Army Staff. Charismatic, strategic, and politically astute, Babangida possessed an unrivalled ability to win loyalty within the officer corps.

His position gave him direct control over the army’s operational machinery, allowing him to place trusted men in key commands months before the coup. He was the public face of the takeover, delivering the broadcast that signalled a new order in Lagos.

Standing firmly by Babangida’s side was Major-General Sani Abacha, then the General Officer Commanding the 2nd Mechanised Division in Ibadan. Abacha was the coup’s muscle — the man responsible for mobilising troops and ensuring no counter-attack could disrupt operations. His reputation for discipline and precision made him the perfect enforcer. Brigadier Aliyu Mohammed Gusau, Director of Military Intelligence, was another pivotal figure.

Gusau ensured that the coup plotters had eyes and ears across the armed forces, monitoring Buhari’s inner circle and intercepting any signs of suspicion. Without Gusau’s quiet but critical role in managing information, the operation could easily have been compromised.

Other notable players included Colonel Tanko Ayuba, who would later become the Minister of Communications, and Brigadier Domkat Bali, a respected senior officer whose support lent legitimacy to the coup within military ranks. The loyalty of the Brigade of Guards, commanded by officers sympathetic to Babangida’s cause, was decisive. Even Commodore Ebitu Ukiwe, a naval officer, was part of the coalition that welcomed the change, ensuring the navy’s stance was neutral and cooperative.

These men, later referred to informally as “the Players of August”, each had their motives — some political, others personal — but together, they formed a formidable alliance that shifted the course of Nigerian history.

Angle, Timing, and Operation of the Coup

The August 1985 coup was not conceived as a bloody showdown but as a calculated palace coup, executed quietly within the heart of Nigeria’s military establishment. The plotters’ angle was clear — they sought to remove Buhari without plunging the country into another cycle of violence. Buhari’s hardline economic policies, his rigid posture on political freedoms, and the perceived drift in governance had alienated key segments of the armed forces.

Babangida and his inner circle positioned themselves as saviours who would restore flexibility and diplomacy in leadership. Their strategy relied less on brute force and more on the precision of military intelligence, secrecy, and the loyalty of critical units.

Timing was everything. The date chosen, August 27, 1985, was no accident. It fell on a Tuesday, a Muslim holiday, ensuring that most political and military actors who could fight them were away from the seat of power. This allowed the plotters to exploit routine movements and minimise suspicion. In the weeks before, Babangida had delicately reshuffled commands and positioned trusted allies in sensitive locations. Communications channels were quietly monitored, and movements of potential opposition figures were tracked.

The early morning hours were selected for the operation, capitalising on the slower tempo of activity in the federal capital at that time. By striking before Buhari’s daily schedule began, they ensured he would be caught off guard, isolated from his support base.

On the morning of August 26, 1985, Sallah day, Muslims gathered at the mosque in Ikeja Cantonment for prayers. Among them were two key military figures: Lt. Col. Sabo Aliyu, Commander of the Brigade of Guards, and his long-time friend, Lt. Col. Halilu Akilu, Director of Military Intelligence. Sabo Aliyu had heard troubling whispers that something unusual was afoot. Several times that morning, he pressed Akilu for the truth. The reply was reassuring — an investigation had been made, and there was nothing to fear. Both men prayed together, neither knowing that before the day was over, they would be on opposite sides of a coup.

The confusion was deliberate. Military Intelligence had disseminated a false story that Colonel Aliyu Mohammed, angered by his forced retirement, was plotting unrest. The claim was a smokescreen, a convenient pretext for mobilising troops in Lagos. All day, the Commander of the Guards Brigade and Buhari’s Aide-De-Camp, Major Mustapha Jokolo, moved between Ikeja, Ikoyi, and Victoria Island, hunting for clarity.

They were unaware that their movements were being watched. Shortly after 9 p.m., as they drove together towards Ikeja Cantonment, they were stopped at the gate by troops under Majors John Madaki and Maxwell Khobe. Shots were fired at their Mercedes, tyres shredded, the men beaten, stripped, and dragged away. Both were locked up in the Officers’ Quarters at Bonny Camp.

By nightfall, Buhari’s isolation was almost total. His Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters, was in Saudi Arabia. His Chief of Army Staff, Ibrahim Babangida, had travelled to Minna for Sallah and could not be reached. His Brigade of Guards commander and Aide-De-Camp were under arrest. The few officers he trusted were either suddenly “unavailable” or openly hostile. Crucially, the National Security Organisation had no combat units, the Minister of Internal Affairs had no troops, and divisions loyal to Buhari were too far away to help.

The coup’s H-Hour began with troops from the 123rd Battalion, 245 Recce Battalion, 201 Armoured HQ Battalion, the 6th Battalion at Bonny Camp, and the 93rd Battalion at Ojo moving into position. Key points — the tollgate, police headquarters, Lagos airport, and major road junctions — were secured. At the Lagos State Police Command HQ in Ikeja, soldiers opened fire without provocation, killing an unknown number of policemen, a reminder that the “bloodless” label often applied to the coup was only partly true.

Armoured vehicles under Majors Khobe and Bulus rumbled towards Radio Nigeria and the State House at Dodan Barracks, while observation posts were set up on key approaches to Lagos Island. In the early hours, startled revellers returning from Sallah celebrations found their routes blocked by tanks, some of which fired into the air to test their guns.

At Dodan Barracks, four Majors — Umar Dangiwa, Lawan Gwadabe, Abdulmumuni Aminu, and Sambo Dasuki — were assigned to arrest Buhari. They met no resistance. The Head of State, aware of the futility of the situation, reportedly ordered his own guards not to interfere. He was first taken to Bonny Camp, then placed under house arrest at 1 Hawkesworth Road in Ikoyi, before later being moved to Benin City. His residence at Dodan Barracks was looted by soldiers.

Meanwhile, Colonel Joshua Dogonyaro entered Radio Nigeria unopposed and, at 6 a.m., read the broadcast announcing Buhari’s removal. By midday, Brigadier Sani Abacha followed with a second broadcast, confirming Major-General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida as Nigeria’s new Head of State and Commander-in-Chief.

So, what were the reasons for the palace coup against Major-General Muhammadu Buhari?

Reasons for the Palace Coup Against Muhammadu Buhari

The palace coup of August 27, 1985, which swept Major-General Muhammadu Buhari out of office, was announced to Nigerians as a patriotic rescue mission. The new regime, headed by Major-General Ibrahim Babangida, claimed Buhari’s government had strayed from the ideals of the 1983 coup that had brought him to power.

In their broadcast, the coup plotters accused the Buhari military government of violating human rights, detaining people without trial, muzzling the press, and executing drug traffickers under retroactive decrees. They also criticised his government for alienating intellectuals, mismanaging the countertrade policy, and pursuing an unpopular loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which they said would have deepened Nigeria’s economic woes. To the public, it was packaged as an intervention to restore hope and fairness.

Yet, behind the scenes, the August 27, 1985, coup was far more personal and calculated. Many of the same officers who overthrew Buhari had been his allies when the military removed President Shehu Shagari in December 1983. At that time, Babangida was Chief of Army Staff, Brigadier Joshua Dogonyaro was a key armoured officer, and Major-General Sani Abacha commanded critical military units. But in less than two years, cracks had emerged.

Buhari’s leadership style was austere and uncompromising. He centralised power, relied heavily on a small circle of trusted officers, and sidelined others who expected influence after the coup. Promotions moved slowly, leaving ambitious younger officers frustrated. There was also growing unease over his refusal to bend to political and economic pressures, a quality his admirers saw as integrity, but his critics called stubbornness.

The spark, according to Buhari himself, was his decision to retire Colonel Aliyu Mohammed Gusau, the influential Director of Military Intelligence. Buhari accused Gusau of receiving illegal commissions from defence contracts, a charge that, if pursued, could have damaged the careers of several top officers. Gusau was a long-time ally and friend of Babangida, and his removal threatened the balance of power within the military hierarchy.

Once Buhari informed Babangida of the retirement decision, the coup machinery began moving in earnest. Intelligence reports suggest that Gusau, aware of his imminent dismissal, urged Babangida’s camp to act before he was officially removed. The plan was simple: seize Buhari quietly before the news of Gusau’s retirement became public, then reverse the decision by executive order under the new Babangida regime.

Babangida would go on to rule for eight years, reshaping Nigeria’s political landscape with a mix of populist charm and calculated manipulation.

For Buhari, it was the abrupt end of his first stint in power, a fall engineered not by public protest or battlefield defeat, but by colleagues he once trusted.

Remembering the Palace Coup Against Buhari: 40 Years Later

Forty years on, the palace coup of August 27, 1985, still invites reflection. Was it simply an internal reshuffling of military power, or did it mark the turning point in Nigeria’s political destiny?

At the time, the takeover was sold to the public as a necessary intervention to save the nation from economic hardship and political rigidity. Yet, did it truly deliver on those promises, or did it pave the way for deeper cycles of instability that would haunt the country for decades? Such questions linger, not merely as historical curiosities, but as reminders of how a single dawn’s events can redirect a nation’s course.

The memory of that morning remains vivid for those who witnessed it. There were no tanks rumbling down the streets in defiance, no prolonged gun battles to seize control; instead, power changed hands almost silently. Could that quietness be interpreted as efficiency, or was it the sign of a system so accustomed to abrupt shifts that resistance felt futile? And what of the players themselves — were they patriots acting in the nation’s best interest, or ambitious officers driven by personal and political calculations? In those moments, the Nigerian people could only watch and listen, their fate decided behind closed doors.

Today, Nigeria stands in a different age, yet the echoes of 1985 still resound. Military coups may have faded from the headlines, but have the lessons truly been learned? Has the nation found the political maturity to guard against such sudden reversals, or does the same vulnerability still lie beneath the surface?

Remembering the August 27, 1985, palace coup against Muhammadu Buhari is not merely about marking an anniversary; it is about understanding how power is taken, how it is wielded, and how the stories of the morning of August 27, 1985, remain woven into the larger tapestry of Nigerian history.

Forty years later, one cannot help but ask: if the conditions were to repeat themselves, would history take the same turn?

Your support can make a world of difference in helping us continue to bring Nigeria’s rich history to life! By donating to HistoryVille, you’re directly contributing to the research, production, and storytelling that uncover the incredible stories of our past. Every donation fuels our mission to educate, inspire, and preserve our heritage for generations to come.

Please stay connected with us through our social media handles and make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel. Together, let’s keep the stories of Nigeria’s past alive.

Leave a Reply

View Comments