No products in the cart.

The United States has witnessed a plethora of Black Race Massacres over the years. From the late 19th century to the 20th century, millions of Black people have lost their lives and loved ones to massacres orchestrated against them as a result of racism and white superiority.

The systemic violence and racism that Black people have faced in the United States of America serve as a reminder of the ongoing struggle for racial justice and equality in the country.

In this article, we bring to you the 10 Worst Black Race Massacres in the history of the United States.

New York (1863)

Also known as the Draft City Riots of 1863, the massacre in New York which took place between July 11 and July 16, 1863, witnessed the death of hundreds of people, albeit the published death count was 119.

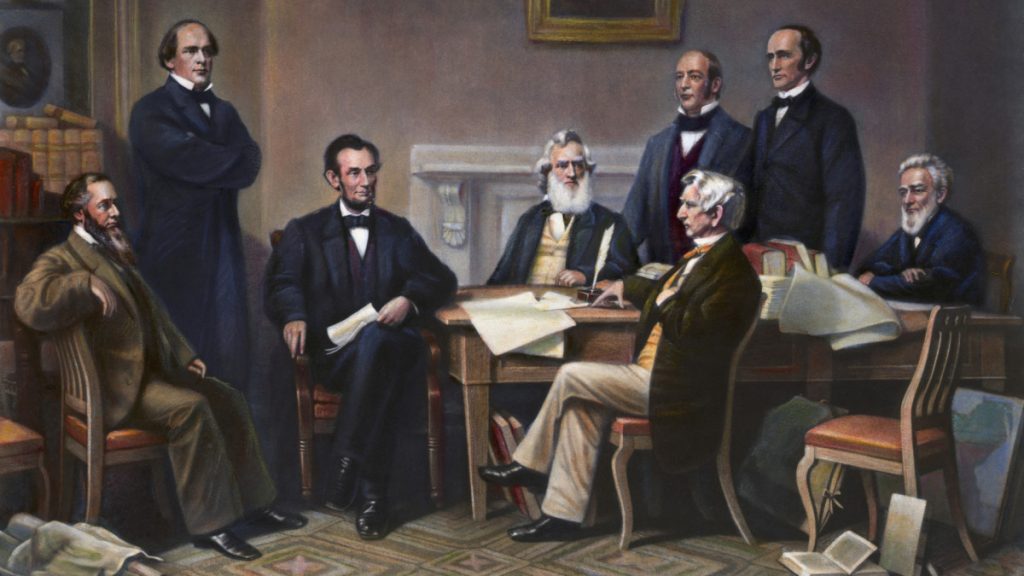

President Abraham Lincoln had, on January 1, 1863, announced the Emancipation Proclamation which saw the end of slavery. Despite its limits, it was praised by the free blacks, slaves and abolitionists, as one of the most important actions on behalf of freedom in the history of the United States.

The Emancipation Proclamation however sparked protests from New York workers, declaring that they would fight to preserve the Union but not to free slaves.

Even though slavery had been abolished in New York before then, the economy of the state was dependent on it. Also at the time, cotton was the main source of income. Cotton accounted for 40 per cent of the shipping in New York’s harbour. There was widespread fear that the end of slavery in the South would increase the competition for jobs. This was further heightened by a sharp recession and widespread unemployment in 1857.

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, the Mayor of New York City, Fernando Wood, called for the city to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy. However, this was met with unenthusiastic responses from most New Yorkers. The fear of competition for jobs had New York’s Irish and German residents on the edge. Black labour competition indicated a reversal of fortunes in New York City.

The straw which broke the camel’s neck was the conscription of men into the army and the eventual escape from conscription by paying a fine of $300.

The draft already built up a form of resentment against the government. The ability to escape drafting by paying the $300 fine further fuelled their resentment. This was because only the rich could afford to pay the fine while the disenfranchised and poor white men were forced to enlist because they could not afford the fine.

The New York draft which started on July 11 saw a relatively quiet city. However, things would change for the worse on July 13 as tensions boiled over.

Thousands of white workers erupted and carried out what was one of the deadliest riotings in the history of the United States.

An orgy of savage murder, arson and looting was the order of the week. Extreme violence was meted out against the blacks, especially the men. The Colored Orphan Asylum, established by Quaker Women in 1936, also suffered the brunt of the pent-up resentment. The building was razed to the ground, but the children were kept safe.

Black men like Williams Jones, Charles Jackson, Jeremiah Robinson, and Abraham Franklin were beaten, mutilated, dragged and killed. Several other people were hanged. The draft headquarters and several other buildings were razed to the ground with damage totalling $1.5 million.

The rioting came to an end on July 16, 1863, after the intervention of federal troops. Several arrests were made but there were no convictions, except for John Andrews, one of the riot leaders who was arrested and jailed.

The Draft City riots were more about economic insecurity and white supremacy. It marked one of the deadliest times in the history of the United States.

Opelousas (1868)

The city of Opelousas, Louisiana, was thrown into a state of turmoil on September 28, 1868, when 29 Blacks were captured, and over the next two weeks, several more were killed. The rioting which spiralled into a massacre came about, first, as a response of the white supremacist group, The Knights of White Camelia, to the actions of Emerson Bentley, a white editor for the local newspaper, The Landry Progress, and an influential schoolteacher.

The April 1868 elections provided the foundation for the Opelousas rioting. The Republicans won in most parishes with a large Black population, but not in Saint Landry Parish. The era following the Emancipation Proclamation and the American Civil War was the Reconstruction period and this saw a lot of Blacks exercise their right to vote.

The White Democrats became fully aware of the voting strength of the Blacks and the future implications that it had for the Democratic Party.

At the time, race was used as a means to gain political ascendency by both Democrats and Republicans. As a result of the April 1868 elections which saw the Republicans win in most parishes, and the forthcoming November Presidential elections, the Democrats began to put measures in place to win the support of the Blacks.

Negro Democratic Clubs were formed with Whites closely supervising the clubs. Negroes were intimidated, albeit in a covert manner. White men roamed the Saint Landry Parish by night, terrorizing the Black population.

In response to the turn of events in the city, Emerson Bentley wrote an article that local members of the Seymour Knights, a branch unit of the White supremacist group, The Knights of White Camelia, thought was a racially inflammatory article.

Having deemed the article offensive, three White men would shortly afterwards, assault Emerson Bentley. He was beaten and this led to him fleeing the city.

The news which made the round was that Bentley had been murdered and the local Blacks sought to retaliate. They would march on to Opelousas where they were met by armed Whites determined to defend their town.

A shooting spree ensued between both parties and 29 Blacks were captured.

The event on September 28 and 29 only marked the beginning of the killings by the Whites. Over the next two weeks, the Whites swept off Saint Landry from one end to another, killing between two to 300 blacks. However, the Democrats refuted this claim stating that only about 25 to 30 people were killed.

The riot only reflected the racial inequality of the nation and further portrayed the ability of the Whites to protect their rights from Black infringement and the Blacks stepping away from their right to vote in order to evade persecution.

Vicksburg (1874)

Following the Emancipation Proclamation and the American Civil War, Blacks began to exercise their right to vote. They began to make progress towards political equality. The passage of “Black Codes” designed to oppress and disenfranchise Black people in the South was not enough to stop them from voting and serving in political office across all tiers of government. At the time, Peter Crosby, a former slave and soldier in the Union Army was elected to office as Sheriff of Warren County. Vicksburg was part of his jurisdiction.

His election into office meant he had to give a bond, as was the custom. He gave his bond, although a majority of the co-signers on his bond were prominent Black citizens. Charged with bogus criminal and tax charges, Sheriff Crosby, on December 2, 1874, was asked to resign by representatives from the Taxpayer’s League, led by John Beard.

Crosby refused to heed their demand stating that he knew no reason why he should. The men left only to come back with a crowd of approximately 600 men. Crosby was ousted from office.

However, he was fully intent on regaining his office. Black individuals organized themselves in an attempt to reinstate Crosby into office.

On December 7, 1874, the group of organized Black individuals would gather in Vicksburg, only to be met by mobs of enraged White men. The mobs brutalised and slaughtered hundreds of Black individuals that day, about 75 to 300 men. Federal troops were assigned to Vicksburg in the aftermath of the atrocity, and Crosby was reinstated as Sheriff. His term was, however, cut short.

In 1875, Sheriff Crosby recruited a white man, J.P. Gilmer as deputy. Soon afterwards, Crosby would attempt to remove Gilmer from office. On June 7, 1875, Gilmer shot Crosby in the head.

Crosby would survive the incident, but he never fully recovered. Although apprehended, Gilmer was never tried for his actions. Crosby would be forced to complete his term via the assistance of a proxy White citizen.

The event of December 7, 1874, would become known as the “Vicksburg Massacre.”

Wilmington (1898)

The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 was a violent attack on the African American community in Wilmington, North Carolina, United States. The event occurred on November 10, 1898, when white supremacists led by the Democratic Party, which had just won control of the state legislature, overthrew the city government of Wilmington, which had been elected by a majority-Black population. The violence resulted in the deaths of an estimated 60 to 300 Black residents, although the exact number is unknown, and the forced resignation of the city’s elected officials, both Black and White, who were replaced by White supremacists.

The incident resulted from a campaign of White supremacy, which had been gaining momentum across the southern United States since the end of the Reconstruction Era in 1877. The Democratic Party, which was then the party of White supremacy, was able to take control of North Carolina’s government in 1898 by appealing to White voters’ fears of Black political and economic power.

The violence in Wilmington was fuelled by a racist editorial in the local newspaper, which called for the overthrow of the biracial city government. This was followed by the arrival of a heavily armed mob, which burned the offices of the Black-owned newspaper and began attacking and killing Black residents. The white supremacists then forced the elected officials to resign, replacing them with their own hand-picked candidates.

The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 is considered one of the most violent examples of White supremacist terrorism in the history of the United States. It had far-reaching consequences, as it helped to solidify the Jim Crow system of racial segregation that dominated the South for decades, and it effectively ended the brief period of political and economic empowerment that African Americans had experienced during the Reconstruction Era.

Red Summer (1919)

The “Red Summer” of 1919 refers to a series of race riots that took place in the United States during the summer of that year. The term “Red Summer” was used to describe the bloodiest summer in the history of the United States, as racial tensions between Blacks and Whites exploded into violence in numerous cities across the country.

The violence was fuelled by a variety of factors, including racial prejudice, economic competition, and a general sense of social upheaval following the end of the First World War. In many cases, returning Black soldiers were met with hostility from White Americans who resented their newfound sense of empowerment.

The most significant of the Red Summer riots was the Chicago race riot of 1919, which lasted for 13 days and resulted in the deaths of 38 people, most of them Black. Other major riots took place in Washington, D.C., Omaha, Nebraska, and Elaine, Arkansas, among other places. James Weldon Johnson, the field secretary to the National Associations for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) termed these riots “Red Summer.”

The Red Summer of 1919 was a dark period in American history, and it serves as a reminder of the deep-seated racial tensions that have plagued the country for centuries. Nevertheless, the activism and resistance of Black people in the face of this violence helped to lay the foundation for the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century.

Washington (1919)

A race riot broke out across Washington, D.C., on Saturday, July 19, 1919. The White mobs attacked the Black communities and their soldiers who had just returned from the First World War, on the account that a Black male had assaulted a White female.

Elsie Stephnick, a 19-year-old was taking a walk from her job to her home when two Black men, reportedly, tried to take her umbrella. She described her assailants as coloured. She claimed she was able to hold them off before a group of White men came to her aid. Stephanie was the wife of a civilian employee of the Navy, and the story broke out among White veterans who were in a downtown bar for a weekend holiday, on Saturday, July 19, 1919. The police arrested Charles Ralls for the crime, but he was later released.

Stephanie’s husband, John was convinced that Ralls was one of the men who attacked his wife. A group of White servicemen met up to exert revenge. The men who had been drinking in a bar gathered in the Black poor neighbourhood of Bloodfield. They beat every Black man they saw until they found Charles Ralls with his wife. They assaulted Ralls and his wife until they were able to break free and ran home where his neighbours defended him.

The violence had grown by Sunday, July 20, as a result of the Metropolitan Police Department’s refusal to intervene. Blacks faced severe beatings by the Whites on the streets of Washington. The attacks took place in front of the White House and the Center Market on Seventh Street. By nightfall, the Blacks had enough and began to fight back. The Blacks, due to the refusal of government officials to intervene, were armed and defended themselves. The police found out that 500 guns had been sold by an arms dealer that day, so they blocked the legal sale of guns. This did not deter the Blacks who sought weapons in the Black market.

Violence continued throughout the night. A Black veteran killed a man in the crowd, and a 17-year-old girl shot an officer who came into her home without a warrant. Both Blacks and Whites were engaged in a heated gun battle and at the end of the night, 10 whites and five blacks were killed or wounded.

On the fourth day of the violence with no police intervention, President Woodrow Wilson ordered 2,000 soldiers from surrounding military bases to go into Washington to bring an end to the rioting. Although, it was a heavy downpour that brought an effective end to the riot on July 23, 1919.

About 150 children, men, and women were beaten by both Black and White mobs. Several men died from gunshot wounds, an estimated 30 people died from other wounds they sustained during riots and nine persons died in the brutal street fights.

In the coming weeks, after the rioters had been dispersed by the rain, Washington had calmed down. The riot was one of the 20 race riots that took place in the period of the Red Summer. Attention had shifted from Washington to Chicago, where a riot had begun.

Chicago (1919)

The Chicago riot of July 27, 1919, was viewed as the most severe of all the riots that took place in the “Red Summer.”

It was a hot Sunday on July 27, and the people of Chicago had gone to the beach of Lake Michigan to find relief from the heat. The beaches had been segregated by custom, one side for Blacks and another for Whites, and this custom was enforced by the police.

A 17-year-old Black man, Eugene Williams and his friends had crossed the invisible line that divided the water by race. A group of Whites, enraged by this act, began throwing rocks into the water. One of the rocks hit Williams in the head and he drowned. Eugene Williams’s murder was what precipitated the Chicago riots of 1919.

The White police had refused to arrest the White man who the Blacks identified as Williams’s killer. It was normal for White officers to ignore White-on-Black crimes in the city. Crowds began to gather demanding that Williams’s killer be arrested. A Black man suddenly opened fire on the police officers but was immediately killed. The Blacks began to attack the Whites and, by night-time, rumours of a race war had been spread in the White neighbourhood. The conflict began. The violence which had begun on the beach spread throughout the south side of Chicago’s Black belt.

The riot lasted for almost a week. At the end of all the sporadic shootings, arsons and beatings, 38 people – 23 blacks and 15 whites – lost their lives. More than 500 persons were injured and Black families were rendered homeless.

Black activists have since then challenged the social hypocrisy of allowing those responsible for Williams’s death to not face justice. These activists continued to clamour against racial discrimination both in Chicago and the United States.

Elaine (1919)

The Elaine massacre of 1919 was one the deadliest and bloodiest racial conflicts to occur in Arkansas and the United States, respectively. At the meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union, a shooting incident took place. The incident further escalated to mob violence. The exact number of lives lost is unknown. It is estimated that hundreds of Blacks and five Whites were killed.

A group of Blacks, who were mainly sharecroppers on White landowners’ plantations met on the night of September 30, 1919, at a church in Hoop Spur Philips County, near Elaine. The union was aimed at helping sharecroppers get fair treatment and wages in their sharecropping jobs. The meeting had Robert L. Hill, a local sharecropper and founder of Progressive Farmers and Household Union.

The union leaders placed armed guards at the front of the church to prevent disruption. About three White males arrived during the meeting to investigate the cause of the meeting. Accounts as to who fired first remain unclear, but the shootings led to the death of two White males.

The news of the shootout reached Elaine. Rumours were spread that the Blacks were planning an “insurrection” against Phillips County White residents. By morning, the Philips County sheriff sent out an arrest for the suspects. The enforcement authorities were met with little resistance from the Blacks, but the Blacks outnumbering them in the area by a ratio of 10 to one led about 1,000 white mobs from surrounding counties of Arkansas to bring down what they termed as an insurrection. Many were from Mississippi and Tennessee. They began killing Blacks and raiding their homes. Some of the Blacks fled from their attackers, while others stayed back and fought.

Governor Charles Brough was contacted through local telegraph operators by the Phillips County authorities to send troops to Elaine. Governor Brough then obtained permission from the Department of War and sent 500 battle-tested troops. When the troops arrived in the morning of October 2, 1919, in Elaine, the White mobs began to disperse for their homes, and hundreds of Blacks were placed in military stockades.

The Blacks kept in the stockades were taken to Helena’s jail. They were 285 in number, but the jail had space for just 48 persons.

According to the testimony of H.F. Smiddy and T.K. Jones, members of the Philips County posse, the blacks were tortured in jail. The Philips County grand jury on October 31, 1919, charged 122 African Americans with murder and racial disturbances. The first 12 men who were tried were found guilty and sentenced to death by an electric chair on November 5, 1919. Sixty-five others, as a result, took on plea bargains. They were sentenced to about 21 years for second-degree murder. The other cases were dismissed.

Tulsa (1921)

The Tulsa race massacre has been described as one of the most severe and horrific incidents of racial violence in the history of the United States. It began on May 31, 1921, and carried on into the next day, June 1, 1921. The prosperous town of the Greenwood district, called Black Wall Street, witnessed the destruction of over 1,400 homes and businesses. An estimated number of 300 people, mostly Blacks, died during the massacre.

A teenager, Dick Rowland, who had dropped out of Booker T. Washington High School to become a shoe shiner in the oil-booming city of Tulsa, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a 17-year-old White girl, in an open wire-caged elevator of the Drexel Building. Once the doors of the elevator opened, he ran out. A clerk in a department store called Renberg, within the building heard Sarah’s screams and called the police. The police arrested Rowland and he was charged with assaulting a White girl.

Although the allegations held against Rowland were never corroborated, it was enough to spike curiosity in some and disgust in others. Before long, after the newspaper containing Rowland’s assault had spread through the city. Twenty-five Black Tulsans had arrived at the courthouse to protect Rowland from the White mob who were rumoured to want to lynch him. They retreated to their district, but a larger group of 75 Tulsans appeared at the courthouse again, after the White mob had increased in size with the authorities not making any move to disperse it. An altercation broke out between a Black and a White man and a shot was fired. All hell broke loose with this altercation.

The whites set fire to most buildings in the Greenwood district. They set fire to a dozen churches, grocery stores, about four drug stores, five hotels and 31 restaurants. The Blacks were outnumbered.

On the morning of June 1, 1921, the National Guard arrived and sent a couple of African Americans to detention centres, holding them for days, weeks, and months in some cases, while the white mob continued to destroy the city.

From the evening of May 31 to the afternoon of June 1, 1921, the mob destroyed the 35 square blocks of the Greenwood community. Homes and businesses amounting to millions of dollars were razed down by the fire. The firefighters who had come to put out the fires were threatened by the White mob to leave.

Apart from the gun battles that ensued during the riots, there were also looting and arson. Precisely 36 citizens – 26 Blacks and 10 Whites, died in the riot. The number has been debated as other sources estimate the death toll from 150 to even 300 people. The discrepancies in the death toll are linked to the unsystematic burial of the victims, as it is believed that some bodies were dumped in the Arkansas River.

Sarah Page did not press any charges against Rowland. After Rowland was released, he left Tulsa and never came back.

Rosewood (1923)

The Rosewood Massacre was a violent and racially motivated attack on the predominantly African American town of Rosewood, Florida, in January 1923. The town was located in Levy County, about 30 miles from Gainesville, and had a population of around 200 people, most of whom were Black. The attack was carried out by a mob of White residents and outsiders, who killed several Black residents, burnt down most of the town’s buildings, and forced the remaining Black residents to flee for their lives.

The incident was triggered by a false accusation made by a White woman named Fannie Taylor, who claimed that she had been assaulted by a Black man. This accusation led to a lynch mob forming, and several Black residents of the neighbouring town of Sumner were targeted and killed. The mob then turned its attention to Rosewood, where they continued the violence, killing at least six Black residents and burning down nearly every structure in the town.

The massacre lasted for several days, and the Black residents of Rosewood were forced to flee into the nearby swamps to avoid being killed. The state of Florida eventually sent in the National Guard to restore order, but by that time, the damage had already been done.

The incident had a lasting impact on the community, as most of the Black residents never returned to Rosewood, and the town was essentially abandoned. The incident was largely forgotten for decades, but in the 1980s, a group of survivors and their descendants began to push for an official investigation and reparations for the victims. In 1994, the Florida Legislature passed a bill that provided compensation to the survivors and their descendants and established a scholarship fund for their education. The incident was also the subject of a book and a movie, both titled “Rosewood,” which brought national attention to the massacre.

Other Black Race Massacres

There are several massacres of Black People in the United States that we haven’t mentioned here. You can let us know about them in the comments.

We always have more stories to tell. So, make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel and have pressed the bell button to receive notifications for interesting historical videos. Also, don’t hesitate to follow us on all our social media handles and share this article with your friends as well.

Feel free to join our YouTube membership to enjoy awesome perks. More details here…

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Leave a Reply