No products in the cart.

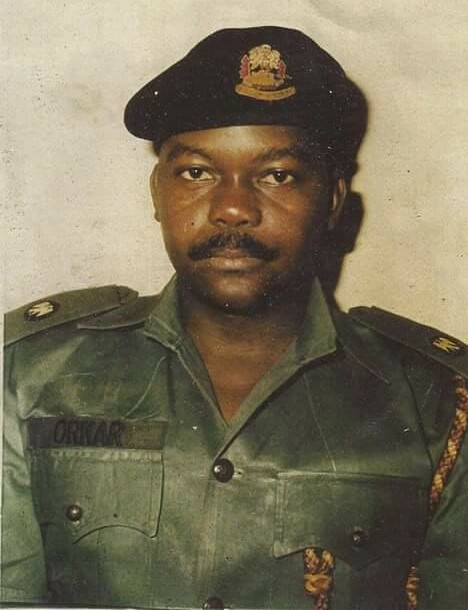

Without General Sani Abacha, Babangida’s military rule would have ended exactly 35 years ago on April 22, 1990, when Major Gideon Orkar made a radio broadcast that denounced the regime in Lagos.

Orkar and his co-conspirators had already captured Dodan Barracks, the official residence of the Head of State, and announced their intentions on national radio.

In fact, without Abacha, they would have overthrown the regime and cut off five northern states from the federation. The political history of Nigeria would have changed forever, but they failed to depose Babangida after the coup was suppressed and eventually crushed by Abacha some hours later.

So, how did Abacha crush the Orkar coup and save the Babangida regime?

Contents

How the Gideon Orkar Coup happened

In the early hours of Sunday, April 22, 1990, at precisely half-past midnight, one of the most audacious coup attempts in Nigeria’s history, the Gideon Orkar coup, commenced. The plotters, a band of young and determined military officers, had just concluded their final strategy meeting at a discreet civilian warehouse located in Ikorodu, Lagos. The premises belonged to a civilian businessman, the enigmatic Great Ogboru—a name that would, in time, become etched into the annals of Nigerian political upheaval.

Presiding over this last briefing was Major Saliba Mukoro, a highly intelligent and meticulous officer from the Military Police, who also held a PhD in Law. At the time, Mukoro served as Military Assistant to the Director of Army Staff Duties and Plans (DASP)—a position ranking just below the Chief of Army Staff within the hierarchy at Army Headquarters. It was a role that gave him not only access but also a measure of influence.

With the briefing concluded, the conspirators dispersed to their various targets—not in official military vehicles, but in unassuming civilian transport, a tactic designed to evade early detection. Their first objective was clear: to arm themselves. This they achieved by swiftly seizing control of the Military Police Barracks in Apapa, a bold move that yielded the firepower they needed.

From there, they moved decisively. Colonels Ajiborisha and Odaro were apprehended and taken under guard to the Ojo Cantonment, where they were detained. Simultaneously, smaller detachments of the coupists were dispatched to strategic locations across Lagos: some to the Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN) station, others to Bonny Camp, while further groups targeted Dodan Barracks—the historic former State House on Ribadu Road and official residence of the Head of State—along with Ikeja and Ojo cantonments. These sites were critical, not only for their military assets but for the symbolic power they represented.

At the FRCN radio station, Lieutenant Okekumatalo of the 123 Infantry Battalion was on duty, yet posed little resistance. For Mukoro, alongside Lieutenant-Colonel Antony Nyiam and Captain Perebo Empere—a fellow Military Police officer—the station was secured with relative ease. Fortuitously, they gained access to a fully armed armoured vehicle, a significant asset in any such operation.

Meanwhile, at the State House, Lieutenant S.O.S. Echendu commandeered an armoured vehicle and, without hesitation, sped towards the radio station. His dramatic manoeuvre likely triggered the first alarms within General Ibrahim Babangida’s residence. Upon Echendu’s arrival, Mukoro redirected him towards Dodan Barracks to reinforce the assault.

It was during this attack that the operation turned deadly. In the firefight that ensued at Dodan Barracks, Lieutenant-Colonel Usman K. Bello, the Aide-de-Camp to Babangida, was killed—a sobering moment that underscored the high stakes of the unfolding drama.

The Assault on Dodan Barracks

The assault on Dodan Barracks, the official residence of Nigeria’s Head of State, unfolded in two distinct and calculated stages.

In the first wave, the plotters executed a cunning strategy: they rendered most of the stationed armoured tanks inoperable by discreetly removing their firing pins. This simple but effective sabotage ensured that even if loyal forces attempted to resist, they would be unable to fire back with any real force.

Then came the second phase—a direct bombardment of the main residential quarters, led by Lieutenant S.O.S. Echendu, who had earlier seized an armoured vehicle and was now spearheading the assault. Explosions thundered through the barracks, shattering any illusion that the coup was a bluff.

Before the shelling began in full, Lieutenant-Colonel Usman K. Bello, the Aide-de-Camp to General Ibrahim Babangida, stepped out of the main quarters, presumably to assess the situation. Dressed in civilian attire and unaccompanied, Bello attempted to climb into one of the disabled tanks, perhaps in a last-ditch effort to mount a defence. But realising the vehicle was useless, he dismounted and began walking alone—towards the direction of the radio station. It was during this exposed walk, under uncertain circumstances, that he was shot and killed, a moment that added both tragedy and symbolism to the failed Orkar coup.

Meanwhile, Captain Kassim Omowa, acting swiftly, evacuated Babangida through a concealed passageway, spiriting him away to an undisclosed location in Lagos where he remained hidden for several days. Other accounts suggest that the embattled Head of State was smuggled out through the rear Ribadu gate, from where he established contact with General Sani Abacha and other loyal commanders.

However, years later, in a 2014 interview with Sahara Reporters, Echendu offered a different version. He claimed he personally saw Babangida escape in a Peugeot 504, yet chose not to open fire. When asked why he spared the life of the country’s most powerful man, Echendu replied with a revolutionary’s restraint: “I wanted the Head of State captured alive and tried for the crimes he had committed.”

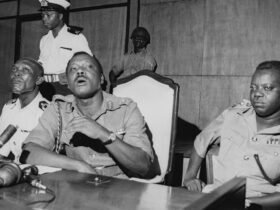

The Assault on Defence House – Abacha’s Narrow Escape

Elsewhere in Lagos, the plotters launched a concurrent attack on another high-value target: the Defence House, located in Ikoyi. Traditionally, this building has served as the official residence of the General Officer Commanding the Nigerian Army since the days of Major-General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi. Over time, it became the residence of the Chief of Army Staff.

By April 1990, Lieutenant-General Sani Abacha—having added the influential title of Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff to his military portfolio—had taken up residence there. It was from this post of strategic importance that he would soon play a pivotal role in quelling the Orkar coup.

Yet fate, and perhaps habit, intervened.

Abacha, a notorious night owl, was not in the building when the attackers arrived. As was his custom, he had retired to a nearby guesthouse for his late-night recreational routines—a well-known fact amongst his aides and close associates.

Led by Lieutenant Henry Ogboru, a Military Police officer and a law student at the University of Benin, the rebel unit reached Abacha’s official quarters only to find it empty. They quickly redirected to the nearby guesthouse, armed and determined. Upon arrival, they opened heavy fire on the guards and the building itself, but in their haste—or perhaps due to lack of thorough military discipline—they failed to conduct a room-by-room search.

That singular oversight would change the course of history.

Hidden within the guesthouse was Abacha himself, alive and unharmed. The rebels’ failure to confirm his death or capture was not merely a missed opportunity—it would prove decisive. From that moment, Abacha moved quickly. As one of the few surviving senior officers with access to communication channels, loyal troops, and command structures, he became the rallying force against the rebellion.

Abacha’s survival not only ensured the physical safety of Babangida but ultimately preserved the regime itself. The Orkar coup had come terrifyingly close to success, but in the end, it would falter—not by overwhelming force, but by small lapses, failed intel, and missed chances.

How Abacha stopped the Gideon Orkar Coup

Roughly 10 minutes after the coup plotters had departed Defence House in Ikoyi, Ibrahim Abacha, the eldest son of General Abacha, arrived at the guesthouse in search of his father. What he found was not a man cowed by an attempted insurrection, but a soldier fully in command of his faculties and intentions.

Without panic or visible agitation, Abacha dressed himself in plain clothes and took up arms. He selected two Uzi submachine guns—one for himself and one for his son. He then instructed Ibrahim to take the wheel of a Peugeot 504 while he took the front passenger seat. Two loyal security operatives occupied the back.

Their first destination was the Flag Staff House. Upon arrival, Abacha issued unequivocal orders to secure the premises, ensuring no further breach could occur. Then he turned to what would become his most powerful weapon in resisting the coup—communication.

Though the rebels had seized several key locations, they had neglected to disable national communication infrastructure. Telephone lines remained active, and more crucially, military signal channels were untouched. Abacha seized the moment. He began calling senior military officers and service chiefs across the country, rallying support, demanding loyalty, and issuing clear directives: the Orkar coup must be resisted at all costs.

As news filtered through that both Abacha and General Ibrahim Babangida were alive, morale among government-loyal units quickly rebounded. Orkar’s incendiary speech—particularly the surreal proclamation expelling five northern states from the federation—had shocked many, but with the top brass alive and issuing orders, officers and troops who might otherwise have adopted a wait-and-see stance began to fall in line.

With armoured vehicles at Ikeja firmly in the hands of pro-Abacha forces, Brigadier Ishaya Bamaiyi led the counter-offensive to reclaim Ikeja Cantonment. This momentum snowballed as key formations rallied to the regime: the 126 Guard Infantry Battalion at Bonny Camp under Lieutenant-Colonel Ghandi Tola Zidon, the 9th Infantry Brigade under Bamaiyi himself, and the Recce Unit at Ikeja. Together, these units mounted a decisive counterattack to retake Dodan Barracks and the FRCN radio station. Some of the rebels were captured, others melted away into the shadows.

The Flight of the Coup Leaders

As the tide turned irreversibly against the mutineers, despair set in among their leadership. At the radio station, where the first announcement of the coup had been made, Lieutenant-Colonel Tony Nyiam and Major Saliba Mukoro—two of the most senior officers involved—briefly considered taking their own lives rather than facing the shame and certain execution of capture.

But instinct for survival prevailed. They fled the radio station under the cover of night and eventually escaped Nigeria altogether: Nyiam to the United Kingdom, Mukoro to the United States. Others followed similar paths.

Among them was Great Ogboru, the wealthy businessman alleged to be a civilian co-conspirator and financier of the coup. He, too, managed to escape to Europe, while Lieutenant S.O.S. Echendu, who had led the assault on Dodan Barracks, made his way to the United States.

With the ringleaders out of reach, the regime turned its attention to those left behind—namely, the families of the fugitives. Security agents detained, harassed, and interrogated relatives in an attempt to extract information or apply pressure through guilt by association.

So, what was the motive behind the mutiny? What did Gideon Orkar and his co-conspirators aim to achieve?

Orkar’s Reasons

In his address on that Sunday morning, Major Gideon Gwaza Orkar attributed the coup to a litany of grievances against the regime of General Ibrahim Babangida. He cited persistent corruption, the mismanagement of the nation’s economy, the assassination of journalist Dele Giwa, and the execution of Major-General Mamman Vatsa—alongside other officers allegedly implicated in an earlier coup attempt—as reasons for taking up arms. These, he said, were clear indicators of a military government that had grown tyrannical, oppressive, and irredeemably disconnected from the people.

But Orkar’s rhetoric went beyond the usual anti-regime sentiment. He painted the coup not as another episode in Nigeria’s long history of military interventions, but as a “well-conceived, planned, and executed revolution”. It was, in his words, a last resort for the “marginalised, oppressed, and enslaved peoples” of the Middle Belt and the South to break free from “eternal slavery and colonisation”—not by a foreign power, but by what he described as “a clique” entrenched in the corridors of Nigerian power.

Orkar laid out three primary reasons for what he and his collaborators believed to be a necessary, albeit radical, action:

- To prevent General Babangida from installing himself as a life president, a move they feared would permanently hinder Nigeria’s development and democratic prospects.

- To end the domination and internal colonisation of Nigeria by a privileged few, particularly a northern political-military elite that the rebels accused of hijacking national power and resources to the detriment of other regions.

- To establish a true federal structure—a foundation for a virile democracy that would reflect the will and diversity of Nigeria’s numerous ethnic and regional identities.

Despite the audacity of their actions, the rebels did not envision themselves as permanent rulers. According to Lieutenant-Colonel Gabriel Anthony Nyiam, the most senior officer involved in the uprising, the aim was to dismantle the existing regime and install a temporary, caretaker government. This transitional authority would be tasked with conducting a credible national census, organising free and fair elections, and initiating a framework for a National Conference to address the country’s structural imbalances.

Remarkably, Nyiam claimed that the rebels had no interest in governing. Their goal was to return power to the people and lay the groundwork for a more equitable, democratic Nigeria. At the centre of this proposed transition was a caretaker committee, which, they stated, would be led by a former cabinet minister from the civilian government of President Shehu Shagari.

In hindsight, whether these intentions were idealistic or simply strategic justifications remains a matter of historical debate. Yet, what is undeniable is that the Gideon Orkar coup was as much ideological as it was militaristic—a rare blend of radical nationalism, regional frustration, and revolutionary ambition.

Why the Gideon Orkar Coup Failed

Despite the audacity and detailed coordination of the April 22, 1990, Gideon Orkar coup attempt, the mutiny unravelled due to a series of strategic miscalculations and operational errors.

Crucially, while the principal conspirators were mostly based in the North—notably in Jaji near Kaduna and Zaria—the plotters made no tangible effort to secure or neutralise military units outside of Lagos, the federal capital. This proved to be a critical oversight. According to Nyiam, a premature leak forced the rebels to accelerate their plans, thereby sacrificing broader national coordination for immediate action to avoid arrests.

The rebels had wrongly assumed that the elimination of General Babangida and General Abacha, alongside the neutralisation of key Lagos-based military installations, would be sufficient to cause the regime to collapse like a house of cards. But this proved to be wishful thinking.

One pivotal turning point in the failure of the Orkar coup was the misstep involving Captain Empere, a Military Police officer and one of the core conspirators. Having helped seize armoured vehicles from the FRCN radio station, Empere drove one of them back to Ikeja Cantonment and opened fire indiscriminately—reportedly shooting at anything that moved until the vehicle ran out of fuel.

However, his primary assignment was not random aggression. He had been tasked with securing and disabling the main battle tanks at the cantonment, which would have been a decisive blow against loyalist forces. His failure to do so was catastrophic for the rebels. It allowed General Sani Abacha and pro-government forces to deploy those very same tanks in a counteroffensive, which ultimately crushed the mutiny.

Aftermath of the Orkar Coup

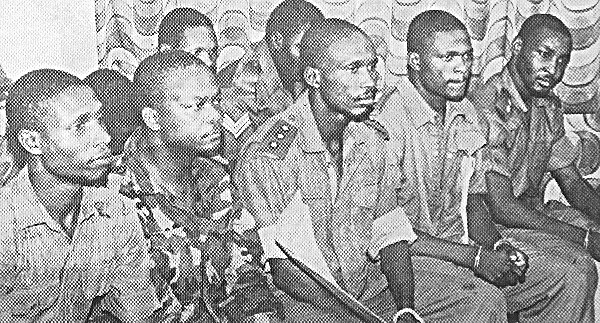

Following the Orkar coup’s collapse, the Nigerian military conducted sweeping arrests. Major Gideon Orkar was apprehended alongside over 300 military personnel and more than 30 civilians. The regime moved swiftly to suppress dissent—journalists known for their criticism of Babangida’s rule were detained, and some newspapers were summarily shut down.

A Special Military Tribunal, chaired by Major-General Ike Nwachukwu, was convened. The outcome was both swift and severe. Orkar and 41 others were convicted of treason and executed by firing squad on July 27, 1990. An additional nine individuals received prison sentences, while 31 soldiers were acquitted.

However, the process was far from transparent or just. According to Human Rights Watch, the accused were not permitted to select their own legal representation, and no appeal mechanism was in place. As the first group of condemned rebels faced execution, some alleged that ethnic bias had played a role in the acquittal of certain co-conspirators.

This prompted the Armed Forces Ruling Council (AFRC) to order a retrial of the 31 acquitted soldiers. A second tribunal, this time led by Major-General Yohanna Yerima Kure, was convened. On September 13, 1990, 27 of the 31 previously acquitted were also sentenced to death and executed. This brought the total number of executions to 69—the highest recorded for any coup attempt in Nigerian history, eclipsing even the 1976 Dimka coup, which saw 39 executed.

Despite their fate, many of the coup plotters remained defiant to the very end. Rather than express regret, the putschists viewed their actions as a necessary stand against tyranny, even in failure. Captain Empere, for instance, boldly declared his admiration for the late Major Isaac Adaka Boro, the Niger Delta revolutionary, whom he called his mentor and hero.

The Coup That Changed Nothing… or Everything?

Was the event of April 22, 1990, a revolution born too soon… or a rebellion destined to fail?

Did Orkar and his co-conspirators truly believe that by capturing Lagos… they could capture the soul of a nation?

Or were they fuelled by a blinding conviction—a noble dream wrapped in strategic miscalculation?

Could they have won… if they had looked beyond the coastline? If they had reached into the barracks of Kaduna, Zaria, and Enugu… would Nigeria have fallen into their hands?

And what of the man who stood between chaos and continuity—General Sani Abacha?

Was it mere fortune that spared his life… or was it his foresight, his ruthlessness, and his command over the levers of power?

Would Babangida’s regime have survived that morning… if Abacha had perished in his guesthouse bed?

Or was it Abacha’s swift moves—his quiet command, his cold resolve—that truly saved the day?

But then… what was truly saved?

Did Nigeria escape the fire… or step deeper into it?

The Orkar coup failed. Yes.

But did it also expose the cracks that still remain?

And for the men who paid with their lives—Major Orkar, Captain Empere, and dozens more…

Were they misguided traitors?

Or patriots who dared to challenge the weight of injustice?

And what of their dream—of a nation free from internal colonisation, of true federalism, of justice for all?

Did it die with them… or does it still whisper through the halls of power, waiting for a different dawn?

History may judge them harshly.

But perhaps… history also listens.

The Aftermath… The Echoes of April 22, 1990, Orkar Coup

The guns may have gone silent, and the radio broadcasts may have faded…

But the Gideon Orkar coup did not vanish without leaving deep scars—political, military, and psychological.

In the barracks, the consequences were instant and clinical.

The Military Police battalions, deemed central to the uprising, were quickly downsized. Trust, once presumed among ranks, was now clouded by suspicion and surveillance. Units once seen as dependable were now considered suspect.

But beyond the barracks… the shockwaves reached far deeper.

The northern political elite, shaken to its very foundation by Orkar’s controversial broadcast, responded with renewed urgency. By the year 2000, the Arewa Consultative Forum was formed—an influential bloc to protect perceived northern interests. A coup that failed militarily… succeeded in awakening regional consciousness.

And then, there was Abuja.

A year after the attempted takeover, General Babangida hastened the move of Nigeria’s capital from Lagos to Abuja in December 1991. The symbolic shift became a physical one—an escape, perhaps, from the ghosts of that night.

But in the process, the Abuja master plan was disrupted, replaced by the necessities of political expediency.

According to Lieutenant Echendu, the coup stripped Babangida of the aura that once surrounded him. The once-indomitable leader had been rattled.

The head of state may have survived… but his confidence did not.

And as one strongman’s shadow receded… another’s grew longer.

Sani Abacha, the quiet saviour of the regime, began his steady rise. From the margins of power, he emerged… until, eventually, he would seize that same power for himself.

And with Abacha as Head of State, came an era of repression Nigeria had never seen before.

Your support can make a world of difference in helping us continue to bring Nigeria’s rich history to life! By donating to HistoryVille, you’re directly contributing to the research, production, and storytelling that uncover the incredible stories of our past. Every donation fuels our mission to educate, inspire, and preserve our heritage for generations to come.

Additionally, if you’re a business or brand, running adverts with us is a powerful way to reach an engaged audience passionate about history and culture while supporting content that matters. Please stay connected with us through our social media handles and make sure you are subscribed to our YouTube Channel. Together, let’s keep the stories of Nigeria’s past alive.

Leave a Reply

View Comments